Home » 2017 Geopolitical Forecast: Middle East and North Africa

2017 Geopolitical Forecast: Middle East and North Africa

> Islamic State becomes stateless

> Internal divisions continue to wrack Iraq

> Syrian conflict evolves but continues

> President Erdogan pushes for a powerful presidency

> Iran holds a presidential election

ISLAMIC STATE LOSES ITS STATE

Despite recent gains in Syria, ISIS will rapidly lose territory in both Iraq and Syria in 2017. With a large number of foreign fighters in its ranks, it will become increasingly reliant on spectacular terrorist attacks worldwide for propaganda value and less focused on insurgent attacks targeting local military objectives.

The Iraq-led operation to retake Mosul is already well underway and will likely succeed in 2017. The fate of Raqqa is less certain in 2017 – while the US and Syrian Kurdish rebels are planning a joint operation to retake the city, renewed cooperation between Turkey, Syria, Iran and Russia could either alter or disrupt these efforts, although anti-ISIS operations from all of these groups will likely continue. The loss of either Mosul or Raqqa, and their surrounding towns, will significantly reduce the group’s ability to control large areas, its ability to launch military offensives, and its revenue raising capabilities.

Over the past few years, ISIS has placed a large emphasis on hijah, or emigration, to Syria and Iraq and has amassed a sizeable contingent of foreign fighters. This strategy is likely to change with the impending loss of Mosul and the possible loss of Raqqa. While ISIS insurgents may continue to find sympathetic towns to fight from, foreign fighters – many of whom have little connection with local populations – are more likely to return to their homelands. This increases the risk of international terrorist acts and will result in an increasingly decentralised organisation. The risk is especially prominent in countries with rising anti-Islam movements, where ISIS will want to drive a wedge between Muslim and non-Muslim populations.

Additionally, with the potential loss of its two major cities, ISIS’ claim to a caliphate will be severely undermined. This could lead to fracturing in ISIS’ ranks. However, a loss of support for the core group will not necessarily reduce the threat of insurgent and terrorist attacks regionally and, to a lesser extent, worldwide. Returning foreign fighters, experienced in combat and with access to extremist networks, may resort to lone wolf terrorism or may even create rival extremist groups.

Overall, despite losing its impressive land holdings, ISIS will continue to pose a terrorist threat worldwide. The group will become more decentralised and more focused on international terrorism as it seeks to retain its legitimacy in the eyes of its followers.

A DIVIDED IRAQ LIMPS ON

Despite being united in their efforts in the fight against ISIS, the militias and security forces that comprise Iraq’s anti-ISIS coalition will compete to fill the vacuum left by the terrorist group in 2017. Iraq, and northern Iraq in particular, will become increasingly divided along sectarian, ethnic and political grounds.

Tensions will likely rise between the central Iraqi government and semi-autonomous Kurdish Regional Government (KRG). Large swaths of land in northern and eastern Iraq are claimed by the KRG, including Kirkuk Governorate and parts of Nineveh, Salah al-Din, Arbil, Diyala and Wasit Governorates. Past efforts to resolve this issue, including a self-determination referendum that failed to transpire, have borne little fruit. The KRG has since been more assertive in its territorial claims.

By displacing ISIS, the Kurdish Peshmerga have steadily consolidated their hold over these disputed territories, which can be used as leverage in any future negotiations. To strengthen their claim to the disputed territories, the KRG will seek to increase the Kurdish populations in these areas while removing other ethnic groups. This process has already begun in Kirkuk where the Peshmerga have evicted local Arab residents, justifying these purges as necessary measures to remove the threat from ISIS.

Disputes in 2017 will largely centre around oil and land. While consolidating its control over residential areas and the nearby oilfields, the KRG will seek more autonomy over oil production and trade. The oil pipeline that connects the KRG territories to Turkey, constructed in 2013, will enable this.

The presence of the Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU), the umbrella organisation of mostly Shi’ite militias, will also stoke tensions with the local Sunni and Kurdish populations. While the central Iraqi government has attempted to bring the PMU under its control since the start of the war, isolated cases of Sunni and Kurdish persecution at the hands of Shia militias remain likely.

To alleviate fears of sectarian clashes, Baghdad and PMU leaders have promised they will not enter the Sunni-dominated city of Mosul. However, these militias will continue to advocate for a more prominent role in Iraq’s security forces and Baghdad will become increasingly unwilling to curb their power – many of these militias have ties to Shi’ite political parties and Iran, a powerful strategic ally.

Militias within the PMU may enter the Syrian warzone after Mosul is recaptured. According to PMU faction leaders, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad called on the PMU for military aid in Syria. However, PMU militia leaders are divided on whether the group should remain a purely domestic force. While some may answer Assad’s call, most of the PMU will likely remain in Iraq.

The threat of Sunni insurgencies will only slightly diminish after the eventual recapture of Mosul in 2017. Rooting out ISIS from the countryside will be difficult and the group’s diminished power will also allow other insurgent groups to grow. Ba’athist militias like the Naqshbandi Army – which has been waging a campaign against ISIS combatants behind enemy lines – will appeal to Sunnis who oppose the PMU and hardline Islamist militias. Young men with past combat experience, and few other skills or employment opportunities will easily be recruited into the country’s patchwork of various militias.

Further south, in Baghdad, political divisions also run deep. While former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki has stated that he will not consider running for office again, his Islamic Dawa Party has been successful in removing a number of Abadi’s cabinet appointments over the past year. In the upcoming 2017 municipal elections, political campaigns will likely capitalise on the country’s many divisions and public protests can be expected in Baghdad and Iraq’s regional centres.

While 2017 will see ISIS-controlled Iraqi territory diminish significantly, internal divisions along sectarian, ethnic and political grounds will likely deepen. Expect to see significant changes in Iraq’s political landscape, with the PMU becoming a more prominent political force and a more assertive KRG calling for greater autonomy. While these changes will likely happen over drawn-out negotiations with Baghdad, some isolated clashes between Iraq’s various militias can be expected.

THE WAR IN SYRIA EVOLVES

Although pro-Assad forces have pushed anti-regime rebels back to their last stronghold in Idlib and some kind of ceasefire is likely, the Syrian conflict will not end in 2017.

With the recapture of Aleppo by the Syrian army, Assad now controls over 40 per cent of the country’s territory, home to 60 per cent of Syria’s citizens. Yet the fall of government-held Homs and Palmyra to ISIS indicates that Assad will continue to struggle to protect and control recovered territory. This is due to two key factors: the predicted uptick in guerrilla warfare as rebels lose ground and overstretching of Assad’s forces as he stays on the offensive.

The evacuation of rebels from Aleppo to Idlib and renewed bombing of Idlib by Russian and Syrian forces in late 2016 suggest that Idlib is likely to become the next critical battlespace. The regime is also likely to try to expand control around Damascus and widen its corridor from Aleppo to Idlib.

The presence of extremist groups in Idlib, with which ‘moderate’ rebels fleeing to Idlib will have to cooperate, could complicate both Western involvement in the war and the peace process. Idlib is primarily controlled by jihadi organisations, including al-Qaeda associate Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (JFS, previously known as Jabhat al-Nusra) and Turkish-backed Ahrar al-Sham (AS).

Significantly, AS has called for a ‘collective leadership’ of rebels that will likely be attempted in 2017. While JFS and AS are united against Assad, they compete for influence within Idlib and will fight for control over any kind of insurgent alliance. With AS undergoing significant internal crisis, JFS is well placed to exert significant control over rebels in Idlib. Though any such coalition will be short-lived and of limited effectiveness due to the serious ideological and strategic differences between and within rebel groups, it could harm the credibility of ‘moderate’ groups and the willingness of Western governments to support them.

It is also likely that Russia and Syria will designate rebel groups cooperating with JFS as terrorist organisations. While JFS is blacklisted internationally as a terrorist organisation, AS is only identified as such by Russia and Syria. Because recognised terrorist organisations can still be targeted under some ceasefire conditions, designating certain groups as terrorists – which are considered ‘moderate’ by other states – will complicate peace talks.

Regardless, Russia, Turkey and Iran will push forward on the peace process, with trilateral talks occurring in Astana in January. At the very least, a symbolic agreement will be reached between the three nations that may then be floated at United Nations peace talks on February 8. Unlike Russia and Syria, Turkey insisted on Assad’s removal as a prerequisite to peace, but has since dropped this request, likely in exchange for Ankara’s other key demands – particularly the exclusion of the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Party and its military arm from the peace process – being met. While an official peace accord may be reached between major parties, insurgencies will continue in Syria throughout 2017.

If the US fails to participate in the peace process and cannot address Russia and Iran’s growing influence in Syria, sectarian tensions in the region will deepen. Despite supporting opposing sides in the war, Russia and Turkey have developed an increasingly robust cooperation on Syria, brokering deals with rebels without US participation.

Ankara’s shift away from Washington and towards Moscow may be perceived by other Western allies in the region as a signal of declining American influence. US-ally Saudi Arabia may become more assertive to kerb gains by regional rival, Iran. Although this may not have any short-term effects on US security alliances in the region, it could weaken the ability of Washington to exert influence in the medium term.

It is likely that 2017 will see the implementation of some kind of ceasefire but Syria will continue to be a deeply divided and destabilised country throughout 2017 and beyond.

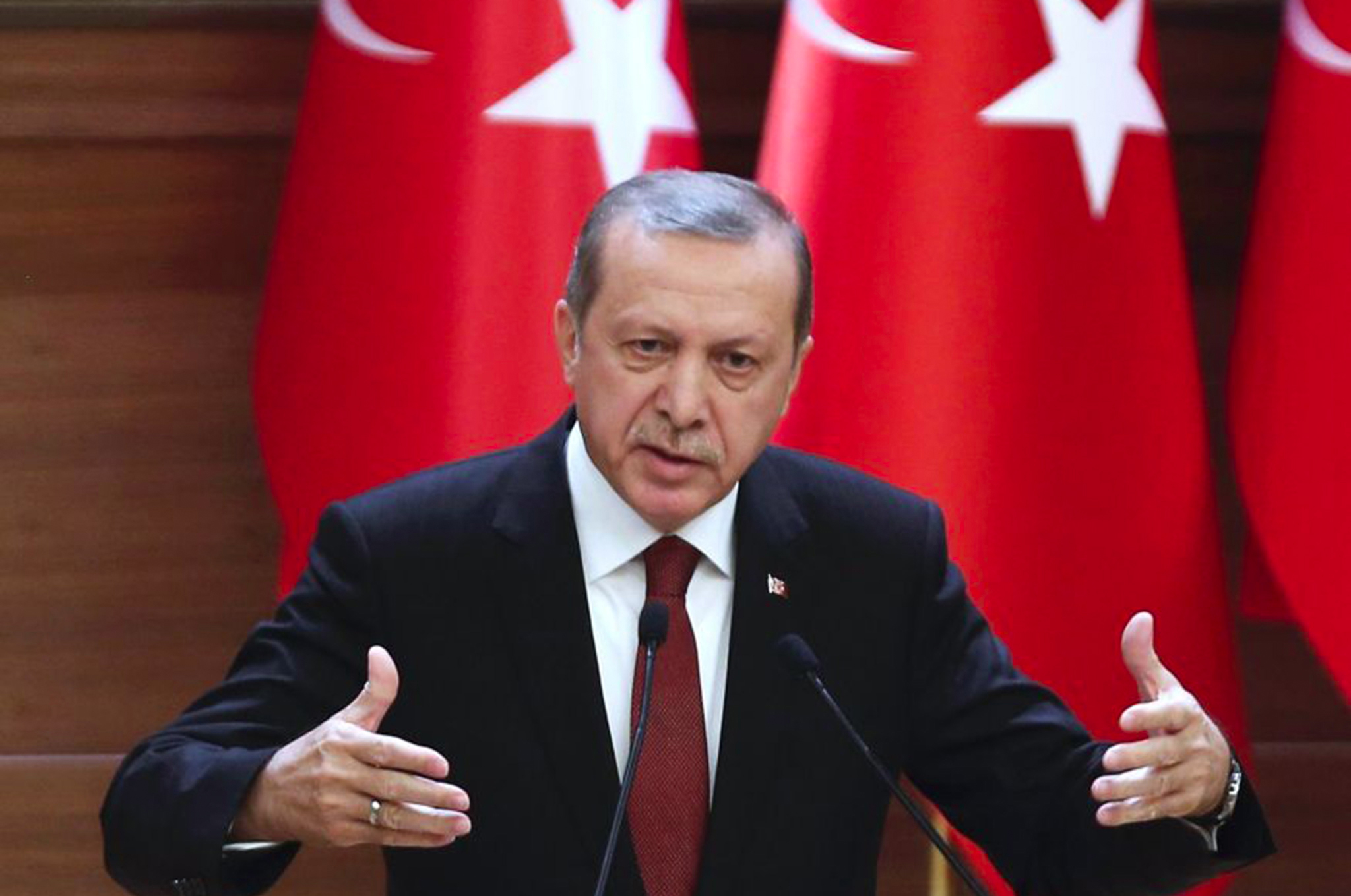

TURKEY’S PRESIDENT CONSOLIDATES HIS POWER

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan will attempt to centralise his power in Turkey by creating a strong presidential system in 2017. While the presidency is officially a weak, ceremonial position, Erdogan has used his immense popularity and political savvy to transform it into the most powerful office in the country. This year he will seek to make that change permanent.

A constitutional referendum proposal, submitted in 2016 by Erdogan’s ruling AK Party in coordination with the right-wing MHP, seeks to substantially increase the powers of the presidency and abolishes the role of prime minister. The reforms also increase the scope of immunities enjoyed by the president and expand the parliament from 550 seats to 600.

Debates will continue until early February, after which a parliamentary vote on whether to accept the changes will be held. The AK Party requires 330 votes to take the reforms to a referendum. With only 317 MPs, the party must rely on support from the nationalist MHP, which has 39 MPs. If, as expected, the proposal receives at least 330 votes, a referendum will be held sometime in April; if it receives more than 367 votes, the changes will be adopted immediately.

Opposition entities outside of parliament may try to resist the reforms. The military, which will be weakened by the proposed oversight mechanisms, may attempt to oppose the measures. However, damaged by purges after the failed coup in 2016, it is unlikely to have the strength to make a major impact.

The Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which has been increasingly violent in the face of Erdogan’s lean to authoritarianism, may also try to upset the process. However, any terrorist attacks would likely help Erdogan rally popular nationalist support and so would be counterproductive.

The referendum is likely to be held in 2017, with the AK Party hopeful it will take place during the summer. If successful, Erdogan will have more power to crack down on domestic opposition. It will also mean he will face fewer obstacles in pursuing a more aggressive foreign policy in the region, with Turkey taking on a more prominent role in neighbouring Syria and Iraq.

IRANIAN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION

Iran’s foreign policy will become even more hawkish in 2017 as Tehran expands its regional influence and negotiates with the incoming anti-Iran Trump administration.

Iran is due to hold presidential elections on May 19, which will likely see current centrist President Hassan Rouhani re-elected. Under Rouhani, Iran’s economy grew 7.4 per cent since the beginning of the current Iranian year on March 20, marking the largest expansion since 2002.

Recent polling indicates Rouhani has the highest support of any current candidates with a 41 per cent approval rating. Rouhani’s nearest competitor, former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, has 29 per cent approval but he has been disqualified from running. Yet much of Rouhani’s support is due to his negotiation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – the Iranian nuclear deal – which will likely to face significant pressure under President Trump.

Under Trump’s administration, Washington could unilaterally withdraw from the deal, seek to renegotiate it, or strictly enforce it in an attempt to pressure Tehran. However, Trump will meet strong Iranian opposition to any changes to the nuclear deal.

Complete withdrawal is unlikely. Instead, the incoming administration may intensify existing sanctions that do not fall under the nuclear deal in an attempt to bring Tehran back to the negotiating table or, at the very least, appear to be taking a stronger stance against Iran. Trump may also seek better oversight over Iran’s nuclear program and stricter punishment for infractions.

However, Tehran’s hostility to any perceived change to the nuclear deal – which was apparent in 2016 when the Iranian leadership protested extensions of the Iran Sanctions Act by the US Congress – makes any renegotiation very difficult. Even in the doubtful case of an American withdrawal, the deal will survive as the other signatories – China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the European Union – will not renege.

Iran’s military support for the Houthis in Yemen will continue, and while ceasefires may be agreed to on paper, neither the Houthis nor Iran will acquiesce to a Sunni majority government. With an embedded Houthi presence in Sana’a and the Saudis continuing to throw their support behind the Hadi government, it is unlikely that 2017 will see an end to this conflict.

‘BLACK SWAN’ EVENTS

– Oman’s Sultan Qaboos bin Said al Said, 76, is reportedly suffering health problems. With no sons of his own, there is no clear succession plan. His death could destabilise the country.

– Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, 77, is also believed to be suffering health problems. His death would prompt Iran’s Assembly of Experts to appoint a new ruler. While the Assembly is elected by popular vote, the country’s Guardian Council, which is appointed by the supreme leader, can disqualify candidates from running. As a result, religious hardliners control the Assembly and they will likely elect a conservative leader in the event of Khamenei’s death.

– Egypt’s weak economy could lead to renewed popular protests and political instability. A struggling tourism industry, austerity measures, and interruptions in oil supplies from Saudi Arabia have been, and will continue to be, a burden on the country’s poor.

– Russia may intervene in the ongoing security crisis in Libya, which enabled ISIS to gain territory in the country. Though the Western-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) has ousted ISIS from its major stronghold of Sirte, much of the country remains lawless, which forced the GNA’s deputy leader to resign on January 2. A Russian intervention would support General Khalifa Haftar, who commands the military forces of a rival eastern government and visited Moscow in November, to expand the territory under his control.