SAUDI IRANIAN RIVALRY FEEDS PROXY WARS

While ISIS’ exploits in the Middle East have captured the world’s attention, it is the geopolitical rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran that will drive major regional developments in 2016. Proxy wars in Syria and Yemen have been fuelled by the two regional powers, which have provided military, logistical and financial assistance to a number of groups on the ground. These conflicts have weakened state structures and contributed to conditions in which militant groups have been able to entrench themselves and further destabilise the region. Although the specifics vary in each conflict, the sway held by Saudi Arabia and Iran will be key to the outcome of regional conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and to a lesser extent Iraq.

2016 will not see an improvement in Saudi-Iranian relations. The strained relationship publicly ruptured in early January 2016 after Saudi authorities executed a prominent Shi’a cleric – a move that sparked angry protests in Tehran, resulting in the storming of the Saudi embassy. This break in diplomatic ties is a symptom of a relationship that has deteriorated significantly in the past few years, primarily as a result of the proxy war in Syria.

Warming relations between the West and Iran – symbolised by the Iran nuclear deal – have also exacerbated tensions between the regional powers. GCC leaders have grown anxious over a perceived about-face by Washington and have begun to question the once steadfast support of their North American ally. As a result, the Sunni Gulf monarchies have pursued more assertive and independent regional policies, highlighted by their campaign to push Houthi rebels out of power in Yemen.

Ultimately, although regional and international coordination may be possible on some limited issues, the trend of worsening relations between the two regional heavyweights will continue well into 2016, an ominous sign for Middle Eastern conflicts.

SYRIA: THE REGIME SEES OUT ANOTHER YEAR

The rise of ISIS has universally undermined regional security. In 2015, the group and its affiliates routinely attacked targets beyond its primary theatre of operations in Iraq and Syria. Notably, ISIS struck politically sensitive sites in both Turkey and Saudi Arabia – two regional powers that have been accused of supporting the extremist group.

These two countries, along with Iran, Russia and a coalition of Western states have been engaged in airstrikes and ground operations against ISIS, creating a rare instance of agreement and alignment of interests in the Middle East. This common enemy presents a limited opportunity to cooperate on the narrow basis of combating ISIS. In late 2015, UN Security Council Resolution 2249 signalled this possibility by highlighting the fight against terrorism as a common interest for all countries.

However, both Russia and the US are wary of deeper involvement in Syria, having both been stung by previous military engagements in the Islamic world. Therefore, it is likely that the two global powers will seek to broker a ceasefire of sorts between their respective allies in Tehran and Riyadh, freezing the conflict temporarily to focus on defeating ISIS.

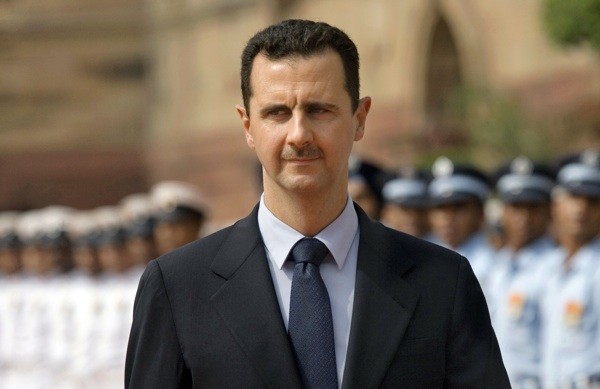

While the geopolitical rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia may not block tacit cooperation on points of mutual interest such as combating ISIS (particularly when external pressure is applied), it will prove an insurmountable challenge to a broader agreement, at least in 2016. Therefore, although cooperation against ISIS could prove to be a valuable confidence-building measure between the Saudis and Iranians, the stark polarisation on almost all other issues – particularly on the future of Bashar al Assad – means that there is little chance for a long-term agreement on substantive political issues. As such, Assad’s embattled regime will remain in Damascus through 2016.

ISIS LOSES GROUND IN IRAQ

In the coming year, developments in Iraq will centre on the effort to rid the country of ISIS. The extremist group lost substantial territory in 2015, including strongholds in Tikrit and Ramadi. This trend looks set to continue in 2016 as Iraqi security forces push to re-establish control of the country, particularly in Iraq’s second-largest city, Mosul, which remains under ISIS control.

However, while it is unlikely ISIS will make any real gains in Iraq, the long-term structural and sectarian difficulties facing Baghdad and the doggedness of ISIS’ resistance means the process will be slow.

These factors mean that ISIS will not be completely expelled from Iraq in 2016

The weakness of Iraq’s security forces in the face of ISIS’ onslaught has been a factor in the group’s rapid rise. Although Western advisers have been deployed to help train and equip the Iraqi military, it is still far from an effective fighting force. This has opened the door for other groups to play a role in military operations on the ground, particularly Kurdish and Shi’a militias. Baghdad’s over-reliance on these Shi’a militias poses the greatest challenge to Iraq’s long-term survival.

Many Shi’a militias are funded, influenced and coordinated by Iran, as evidenced by sightings of the commander of Iran’s Quds Force, General Qasem Soleimani, on Iraqi battlefields. The effectiveness of these forces in fighting ISIS has given Iraq’s powerful Shi’a neighbour significant leverage in Baghdad. This, in turn, has exacerbated already strained tensions between the minority Sunni population and the majority Shi’a, particularly after allegations that Shi’a militias engaged in extra-judicial killings against Sunnis during the recapture of Tikrit.

Although Prime Minister Abadi has adopted a more inclusive approach to governance than his predecessor Nouri al Maliki – allowing Sunni tribesman to take part in the recapture of Ramadi, for example – the festering sectarian wounds inflicted by the former administration endure. These issues will continue to undermine and challenge the cohesiveness of the Iraqi state and will remain deeply entrenched throughout 2016, although a return to the civil war-like conditions of 2006-7 is unlikely.

Significantly, even in the unlikely event that security forces succeed in expelling ISIS from Iraq, the group’s enduring presence in neighbouring Syria will continue to pose a direct threat to Iraqi security. In this sense, the fight against ISIS in Iraq is both inextricably and geographically linked to the group’s fortunes in Syria, particularly as the border between the two countries is virtually non-existent in its present state. Therefore, the two conflicts require a coordinated response, something that is highly unlikely given the current regional climate.

SAUDI STRATEGIC OVERREACH IN YEMEN

Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen is indicative of the newfound assertiveness in the Kingdom’s foreign policy. Riyadh and its GCC partners have justified the conflict as a mission to restore the government of President Abbed Rabbo Mansour Hadi, who was ousted by Houthi rebels in early 2015. This more muscular approach appears to have led to Saudi strategic overreach in Yemen, with Riyadh finding itself increasingly drawn into a complex conflict with no quick or easy resolution.

Although Saudi Arabia and its GCC allies insist the Houthis are Iranian proxies, the degree of control Tehran actually wields over the rebel group has been exaggerated. The Houthis have received financial and military support from Iran, but that has not resulted in Tehran exerting direct influence over the rebel group, a reality highlighted in 2014 when Iranian leaders called on the Houthis not to enter the capital city of Sana’a only to find their request ignored.

In 2016, the war in Yemen will continue to drain Saudi resources, as well as the monarchies’ domestic political capital. This will be exacerbated if the Saudi casualty rate continues to climb. If this happens, Riyadh is likely to double down on its efforts in Yemen, being further drawn into the difficult conflict and diverting attention and resources from other regional hotspots. However, as the war is mainly conducted by way of airstrikes and mercenary forces, and with only a small number of Saudi troops on the ground, the likelihood of the Kingdom suffering large losses is small.

Ultimately, the continuation of the conflict in 2016 will result in a stalemate that will pin down Saudi Arabia and produce a worsening humanitarian situation but result in little in the way of a regional power shift or political solution within Yemen itself.

As a poor country with a young population who have lived with conflict for many years, Yemen has long been a hotbed for extremist Islamic militants and is home to a sizeable contingent of forces loyal to al Qaeda. The worsening situation in Yemen will exacerbate this problem, driving young men to extremism and into the ranks of extremist organisations. As a powerful and expansive regional actor, ISIS will seek to capitalise on this and increase its presence in Yemen in 2016.

AN UNPOPULAR PEACE IN LIBYA

A peace agreement signed in December 2015 does not appear to have the support on the ground that the UN Security Council and international community would like to believe. The signed unity deal appears to be positive at first glance, but once several aspects of the deal are analysed, the chances of an enduring solution to the country’s problems begin to look rather unlikely.

The deal was signed by only 88 of 200 parliamentarians from the Tobruk and Tripoli governments and was opposed by the heads of the internationally recognised parliament in Tobruk (who voted against the new unity government on January 25, 2016) and the rebel-backed authority based in Tripoli. The unity government deal was signed by the deputy speaker and second deputy speaker respectively. It had been criticised by the speakers of both parliaments, which casts significant doubt over the legitimacy of the peace agreement.

The agreement would establish a nine-member council representing various Libyan factions and regions, and aimed at bringing together the various conflicting views and groups within the country. However, while signing the agreement was a positive development in its own right, its implementation will prove to be far more challenging than the UN Security Council is willing to admit. General Hifter, previously the Tobruk government’s military man, was given the role of the unity government’s military leader. However, he will be unable to expand the writ of the unity government beyond much of eastern Libya. With ISIS firmly entrenched in areas such as Sirte, and Derna, Hifter will likely receive weapons and training from the West. However without significant air support from Western powers, this alone will not prove to be enough to erode ISIS capabilities, or indeed, its territory.

Western airstrikes in Libya will not materialise in the first half of 2016. Rather, the international community will give the UN-backed government time to find its feet. The new Libyan unity government may ask for support should ISIS begin to expand its territory considerably, a likely development. Any airstrikes from the Western powers are likely to complicate the situation even further – with the various groups with different backers fighting over key areas, with no side strong enough to emerge victorious.

On the other side, ISIS has gained a vital foothold in Libya, where its presence has expanded in the past twelve months and will continue to do so in 2016.

Taken at face value, the power-sharing agreement signed in Morocco in December between the rival governments in Tobruk and Tripoli should pose a threat to ISIS in the country. In fact, the opposite is true. The Morocco agreement will not create a cohesive Libyan government that will be able to overcome its internal disagreements sufficiently to pose an existential threat to the Libyan branch of ISIS. In turn, ISIS will capitalise on the weakness of the Libyan state to consolidate its control over areas such as Sirte, while seeking to expand towards oil pipelines and infrastructure in central Libya. The capture of such facilities would hasten Western intervention, particularly from a naval standpoint, which would seek to disrupt any attempt by ISIS to ship its illicit oil by sea

ISIS will use the first months of 2016 to evaluate the strength of the new unity government, and will quickly conclude it will be in a position to exploit instability arising out of infighting or a Western intervention, which will occur later in the year. With various factions opposed to the UN-backed agreement, there is a considerable chance that ISIS will attract more local recruits, which would provide a steady supply of locally-sourced fighters

Simon is the founder of Foreign Brief who served as managing director from 2015 to 2021. A lawyer by training, Simon has worked as an analyst and adviser in the private sector and government. Simon’s desire to help clients understand global developments in a contextualised way underpinned the establishment of Foreign Brief. This aspiration remains the organisation’s driving principle.