Home » The DRC’s ongoing battle with the Ebola virus

The DRC’s ongoing battle with the Ebola virus

WHAT’S HAPPENING?

Medecins Sans Frontieres has suspended its medical services in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) after its treatment centres were attacked. The region is experiencing its worst ever Ebola outbreak.

KEY INSIGHTS

– The outbreak of the Ebola virus disease in the DRC has increased population movements, further straining an already fragile political situation

– Accessibility to the affected region is hampered by political unrest and violence

– The virus has the potential to spread to neighbouring Uganda, South Sudan and Rwanda

– Preventative measures to reduce the virus’ spread through an unlicensed vaccine have so far been successful

The Ebola outbreak, coupled with heightened political tensions, has led to a difficult security situation in the north-eastern provinces of the DRC. This is the world’s second-largest Ebola outbreak after the 2014-16 epidemic in West Africa. As the outbreak enters its seventh month, the situation is becoming ever more serious.

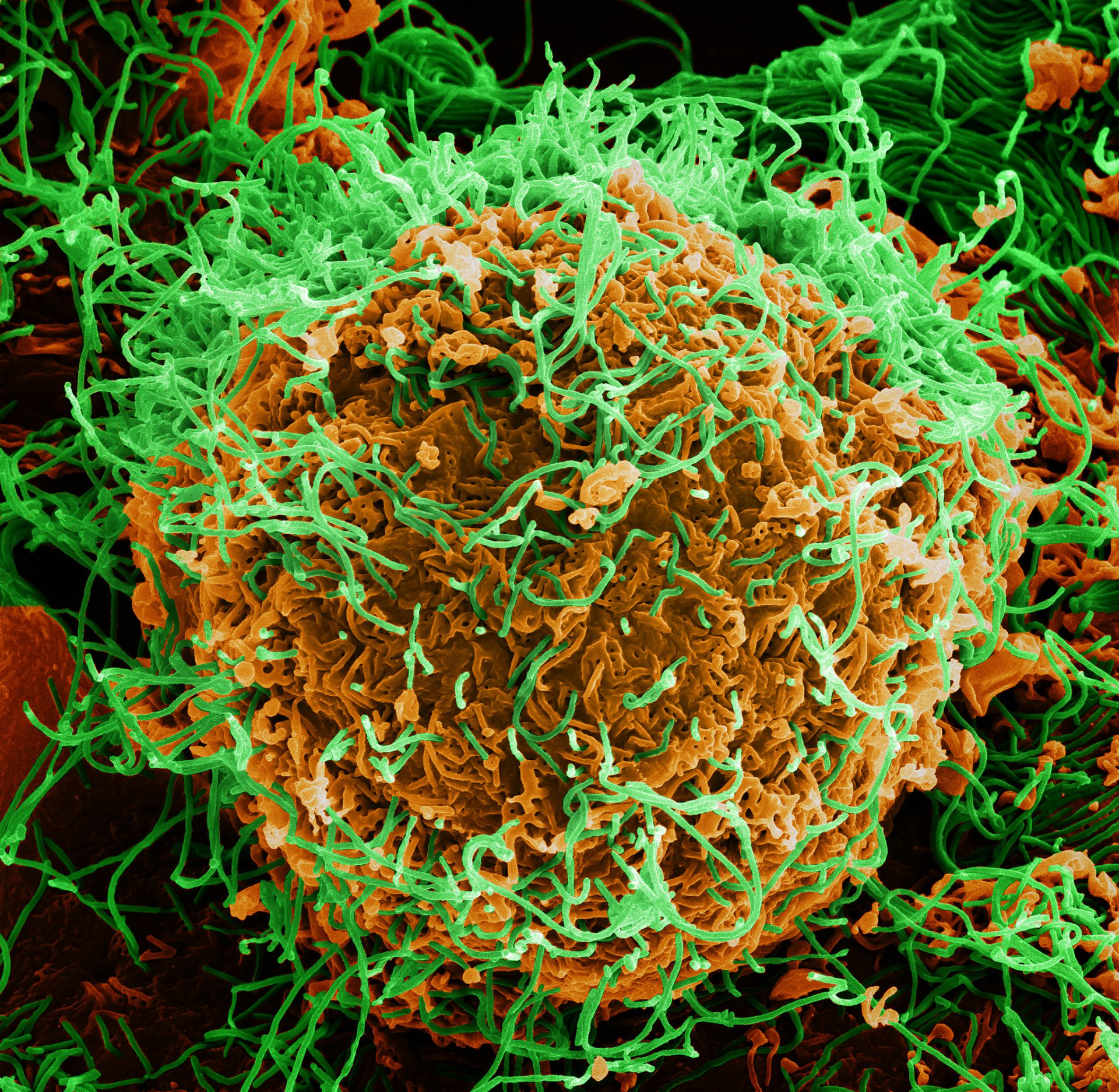

THE DRC’S LONG RELATIONSHIP WITH EBOLA

Ebola, which has no known cure, first appeared near the Ebola river in the DRC in 1976. The country is now experiencing its tenth and largest outbreak. The virus is initially transmitted to humans from fruit bats or other infected animals through close contact, such as handling or ingestion. It can be difficult to detect, as the first symptoms — a fever, muscle aches and sore throat — are not specific to Ebola. The disease is therefore often initially confused with other more common regional diseases like yellow fever, malaria or meningitis.

As a person becomes sicker, they become much more infectious, with the rate of transmission peaking during the later stages of infection and after death. Stopping direct human-to-human transmission is therefore essential to controlling an outbreak. However, burial rituals in the DRC involve touching and washing the deceased body, which can often lead to contraction of the disease. The cultural shift needed during an Ebola outbreak can create distrust between communities and responders. In the DRC, this has manifested in locals attacking Ebola treatment centres.

VIOLENCE AND ELECTIONS

Persistent violence in the eastern DRC is the main reason behind the disease’s spread, as insecurity has limited accessibility and prevented medical resources getting to those who are at risk of contracting Ebola. However, this is a cycle: Ebola’s advance is also increasing conflict as panic spreads and political opportunists capitalise on community fears. The outbreak prompted the government to postpone voting in the eastern provinces for the already controversial December 2018 presidential election. This led to a backlash against Ebola treatment centres, especially those located in the city of Beni. Protesters attacked multiple centres and some individuals involved could have contracted the disease. The damage to these centres significantly set back the healthcare services available in the region and responders’ ability to screen and isolate suspected Ebola cases.

Although the North Kivu and Ituri provinces have been embroiled in political violence for the last 25 years, tensions spiked again after the announcement of the election results. Opposition candidate Felix Tshisekedi claimed victory with 38% of the vote but his win was strongly contested by the Catholic Church, the only credible independent observer to the polls. The result was also denounced by militias and rebel groups in the north-eastern region, sparking another round of violence.

Rural, militia-controlled areas have been particularly difficult to access and assess. The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a terrorist organisation associated with the Uganda Muslim Freedom Fighters, has been increasing its presence in north-eastern DRC. The ADF has been held responsible for multiple peacekeeper deaths and with continued instability in the region, the group has an opportunity to gain more influence and territory. The ADF’s presence has greatly limited the ability of responders to deliver resources into their territory and denied crucial medical care for those with Ebola.

A POPULATION DISPLACED

The conflict in the eastern DRC has already displaced hundreds of thousands of people, exacerbating Ebola’s spread. The ongoing conflict and the growing outbreak have further fuelled the mass displacement, both in the DRC and spilling over into neighbouring countries. Uganda is particularly vulnerable, as it borders the North Kivu region and there is a long history of trade and high population mobility between the two countries. These threats led the World Health Organisation (WHO) to assess that the risk of the outbreak spreading, both regionally and nationally, is very high.

The continued level of violence and increasing displacement has affected the country’s food security. The World Food Programme estimates that more than 100,000 internally displaced people in the South Kivu region cannot be accessed and given needed food assistance. This has led more people to move for food, increasing the disease’s spread. Adding to the medical challenges, populations already weakened from malnutrition and famine are more susceptible to contracting the Ebola virus.

Tracking is essential in Ebola outbreaks in order to predict where the next outbreaks will be. This allows the use of preventative actions (like vaccines) and the screening of those who have been in contact with an infected person. But tracking in the DRC has been made difficult but the mass displacement. Small clusters of the disease have appeared all over the two provinces, although it appears to be moving south towards the provincial capital.

THE UNLICENSED TREATMENTS

First-line responders to the crisis have been given an unlicensed vaccine, rVSV-ZEBOV, as a key preventative measure. There is supporting evidence that the vaccine — developed from research conducted during a previous Ebola outbreak in Guinea — is effective in preventing this strain of the Ebola virus (Zaire Strain). However, the shift to using clinical trials during an outbreak is a new and controversial approach from the WHO because the drug is still being tested for its effectiveness and side-effects. Such drugs normally go through randomised controlled trials, which require a ‘control group’ that does not receive the treatment. But creating control groups during an epidemic leaves individuals at high risk of contracting a potentially fatal disease.

It’s not clear whether this trial setting has been implemented in the DRC in the current outbreak. Currently, the vaccine is available to those who have been in direct contact with someone infected, but accessibility and tracking constraints render implementation difficult. One major limitation is that the vaccine needs to be stored at -60 degrees Celsius, a high barrier for safe delivery to those in rural areas.

Medicins San Frontieres has identified five potential drugs for the treatment of Ebola, however, they have not passed all steps of clinical testing. Three of these drugs are slowly being made accessible through randomised clinical trials and only with the informed consent of the patient. However, in previous outbreaks (such as in West Africa, 2014) there have been issues with funding for these medications. As the drugs are designated for treatment rather than prevention, it has been more difficult to administer to patients, and as such these trials have only been implemented at a few key treatment centres.

The Ebola virus remains a serious security and health threat to the region. The outbreak is likely to continue until into June 2019, based on the current rate of transmission. Aid and medical services will continue to be limited by security conditions devolving from civil unrest and violence in the north-eastern provinces. The violence will also thwart essential prevention measures, like disease tracking, from being successfully implemented. As such, expect the Ebola outbreak to continue to spread and the casualty count to grow.

Isabel is a risk analyst in the Asia-Pacific team. She covers health and environmental security issues in the Indo-Pacific region.